Chu Shogi

Chu Shogi ('Middle Shogi') has been the dominant form of Chess in Japan for many centuries, until the invention of piece drops caused it to be replaced by modern Shogi. The first mentioning of it in historic documents, as an already popular game, occurred around 1350 AD. It was probably derived from a larger game, Dai Shogi ('Large Shogi'), by abolishing the eight weakest piece types (16 pieces) that all promoted to the same, rather weak piece as Pawns already do, and putting the remaining pieces on a smaller board. Due to its long history and large popularity the rules have been very much refined. At some point the game got nearly extinct, and the rules forgotten. Historic records of several games have survived, however, as well as four collections with a total of 224 mating problems, some including solutions as well. As a result it is now pretty well known what the historic rules were.

Chu Shogi is played on a 12x12 board with initially 46 pieces of 21 different types on each side. But what makes the game really interesting is a single super-piece, the Lion. Chu Shogi without Lion is somewhat like modern Chess without a Queen: it loses much of its glamour, and becomes a lot more tedious and boring to play. And the Lions are so dominating that they will quickly encounter each other, so that a quick trade would be quite common. For this reason there is a set of additional rules concerning capture of Lions that makes such trading very difficult. This ensures that in most Chu Shogi games the Lions survive until the end-game.

Rules PDF and Cutouts for playing Chu Shogi over-the-board

Chu Shogi Applet for playing without Internet access

Play Chu Shogi against the computer through Jocly

Play Chu Shogi against others via Game Courier

Setup

|

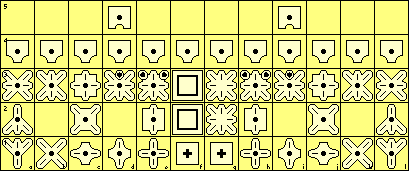

Lines below can be clicked to see how the pieces move: |

|

First rank

|

Second rank

|

Third rank

|

Fourth and fifth rank

|

Pieces

The large majority of pieces has moves that either step or slide along orthogonals and diagonals. (They can slide in some directions, and step in others, though.) Other leaps are rare; oblique leaps do not occur at all, and leaps to the second square (Betza A and D) are rare. The moves of these 'normal' pieces are given in Betza notation above, and should furthermore be obvious from the mnemonic piece pictograms. The pieces with special properties, which spice up the game, are discussed below:

Lion

- move or capture by leaping to any square in the 5x5 area surrounding it,

- capture an adjacent piece, and then go on moving or capturing once more as a King,

- move to an adjacent empty square and back, effectively passing a turn.

Horned Falcon, Soaring Eagle

The Falcon and the Eagle, only available through promotion, have a limited form of Lion Power. They can make up to two steps, continuing after a capture, but only along the same ray. So for the (optional) second step they can only decide if they want to continue in the same direction, or move back to their starting square. Like Lion moves, a double-step to another square can also be taken as a direct leap, but returning to the starting square can not, but needs the adjacent square either to be empty or contain an opponent (which must then be captured). The Falcon and Eagle have such a move only in one, respectively two of the eight directions, and slide in all other directions.

Rules

Goal

The game is won by eliminating the opponent's royal piece(s). Royal are King and 'Prince', the latter being a second King obtainable through promotion. There is no rule against venturing into or leaving yourself in check, although this would of course be unwise. This makes stalemate non-existent in real games, and if there ever has been a rule for it, it is no longer known. For definiteness we can assume that stalemate is a win.

Promotion

Like in most Shogi variants, it is not just the Pawns that can promote, but almost all pieces. There is no choice for what to promote to: each piece type has a pre-determined promoted form (written on the back of the tile used to represent the piece, so that it can be flipped to perform the promotion). They often promote to a piece that was already present in the initial setup. But in that case it cannot promote again, even if the latter does: every piece promotes at most once. So a Rook obtained by promoting a Gold is really a different Rook from the one present initially, as the latter can still promote, and is thus much more valuable.

Pieces can promote when they enter the promotion zone formed by the furthest four board ranks. This is optional; you can always defer promotion, and in some cases that makes sense, because not all promoted pieces are strictly upward compatible with their unpromoted forms. In addition, moves that start inside the promotion zone can lead to promotion when they capture something. The rule of modern Shogi that any move that touches the promotion zone (i.e. enter, leave or move entirely inside it) can be played as promotion is apparently a later invention, which became necessary when pieces could be dropped in the zone, but was never used in Chu Shogi (as many of the historic mating problems demonstrate).

Pieces promote as follows (moves only indicated for pieces not occurring in the initial setup):

|

One army with all pieces promoted |

There is a special rule for Pawns: when these reach the last rank, they are allowed to promote even on a non-capture. No such exception exists for other pieces, not even the Lance, which also can never leave the promotion zone once it entered. As the Lance promotes to a stricly upward compatible piece, there never is any reason to defer promotion of it, so it was apparently felt that if you were silly enough to defer Lance promotion, it was your own fault it could end up as dead wood. (For Pawns there can be reason to defer promotion, which has to do with the restrictions on Lion capture.)

Prince

The Elephant promotes to Prince, which is just another name for King. So you can have two royals in Chu Shogi. This counts as extinction royalty, i.e. when you have two royals, one of them can be captured without ill effects, and only when your last royal is captured you lose the game.

Restrictions on Lion trading

To conserve the Lions, there are restrictions on capturing those, aiming to prevent elimination of two Lions in consecutive turns. Roughly speaking, this needs two rules, one against direct trading, one against indirect trading:

- A Lion cannot capture a Lion if that would expose it to recapture in the next turn, as if it had become an absolute royal for one turn. ('protected')

- A non-Lion cannot capture a Lion when on the previous turn a Lion was captured by a non-Lion on another square. ('counter-strike')

- You can always capture the opponent Lion with yours when it is adjacent, and thus could be taken in passing, rendering any protection ineffective.

- If you capture another piece together with the opponent Lion, you can even do it when your Lion can be recaptured.

- This additionally captured piece must not be a Pawn or Go Between, though.

Repetitions

Historic descriptions of Chu Shogi mention that repeating a position that occurred previously (with same side to move) is forbidden. They don't specify which player carries the burden to change his move, though evidence from historic mating problems suggest that the rule does not apply to players who are in check.

The Japanese Chu Shogi association applies the following rules (which might be more elaborate than the historic rules):

- In case of a perpetual check, (i.e. all moves since the previous occurrence are checks) the checker must change his move from the repeated position, or lose.

- In case one side attacked pieces (no matter how futile) with any of his moves since the previous occurrence, and the other doesn't, the attacker must change his move or lose.

- If both players are passing turns, the one that started passing must change his move or lose.

- In case no one attacks anything with any of his moves, a draw can be claimed in the repeated position.

- In all other cases, the repetition must be avoided, i.e. the side playing the move that brought it on the board will lose due to an illegal move.

King Baring

Historic documents mention that King + Gold versus King is a win. It is not clear whether this was meant as a rule, as a courtesy custom, or just as an example. What makes it puzzling is that this end-game is trivially won anyway, as the Gold promotes to Rook, and KRK is an easy win on any size board. And the text explicitly states that this applies to a primordial Gold, rather than a promoted Pawn (Tokin). For a Tokin the rule would make more sense, as the Tokin has no mating potential on a 12x12 board. Some people have interpreted this remark as the rule that you can in general win by baring the opponent King, as in Shatranj. This would affect the 2-vs-1 end-games with promoted or unpromoted Pawn and Leopard, as these are the only pieces that do not have mating potential and do not promote to a piece that does. (And Tiger, Silver or Copper can sometimes be chased towards an edge to be captured there, when separated from their King.) It seems a bit unlikely that the author for describing such rule would only mention Gold, and not just Pawn and Leopard, or simply say 'any piece'. Nevertheless, the Japanese Chu Shogi Association seems to have adopted the rule that you can win by King baring, unless in the immediately following move your King is bared too (or captured to leave you without royal).

Notes

Basic strategy

In Chu the strong pieces stand immediately behind the Pawns, and the weak steppers stand in the back. This is actually a very vulnerable situation, as the steppers, weak as they are, have much more dangerous forking power as FIDE Pawns, and exposing your precious sliders to them is a very bad idea. Chu games therefore typically start by developing the steppers, in particular Leopard, Silver and Copper, by moving them to the 4th rank, before your sliders. To create space for this the Pawns are moved up to 5th rank, and then some of the sliders to 4th rank, in order to create corridors on the 3rd rank through which the steppers could pass.

Golds are better left in reserve for the end-game, as they have a very valuable promotion (to Rook). The same holds for Kirin and Phoenix. They are tactically somewhat more powerful than steppers, with their jumping moves. But they promote to overwhelmingly strong pieces, so you will be really sorry if in the end-game you don't have them, and the opponent does.

Side Movers are ideal for moving up to the 4th rank, as they will then protect that rank against enemy penetration, of which Lion penetrations would be the most feared. No matter how powerful the Lion is, it remains a short-range leaper, and cannot jump over two protected ranks. So as the board empties, you will typically use your Side Movers to cover 3rd and 4th rank, to keep the enemy Lion out of your camp.

Moving next to an enemy Lion (or staying there when the latter moves next to you) is usually suicide, and makes you disappear without a trace. Keeping a closed rank of Pawns, and protecting them from behind, makes the Pawns invulnerable to such a Lion attack, as the Lion can no longer step diagonally next to them.

As the board gets empty it will be impossible to prevent promotion of forward sliders. Steppers are much more difficult to promote, as even when you have a majority of them the first ones approaching the zone will invariably be met by an opponent stepper, which can get there faster because it was closer. So it will take very long before you can make your excess being felt. You should thus be very careful in trading promotable sliders (and especially the Dragon and Horse, which gain a lot on promotion) for non-sliding material, even when at that stage of the game the steppers would be stronger. It will mean your doom in the end-game. But on the other hand, be careful not to count yourself rich by future promotion gain, if what is actually on the board leaves you at such a large disadvantage that you will not survive to see that gain.

It is sometimes tempting to rampage the opponent's wings with a Lion, when he leaves his guard down and allows you to enter his camp. But be careful: it is easy enough to grab a measly Lance an Chariot, as they cannot leave the edge file. But the retreat of an unsupported plundering Lion can often be cut off by the defending Lion, and (when protected) the latter will be able to attack you without having to fear the reciprocal attack, as you will not be allowed to trade Lions. When you get in with a Lion, be sure that you can get out again!

Kings are typically shielded from danger by fortresses built from a line of Tigers and Elephant on the second rank. The configuration with the Tigers next to each othe and the Elephant on one side is a bit better as that with the Elephant in the middle, as when the middle piece is pinned on your King along a file, the blind spot of the Tigers becomes undefended, and a Lion there would deliver checkmate. An Elephant does not have such a blind spot, so you then have the problem only on one side. Golds in the wings of your fortress on the 2nd rank are useless, as a Lion creeps diagonally behind them, to annihilate them on the next move by hit and run. There is no hurry in building the fortress, as initially there is so much heavy material in front of your King that the opponent cannot get anywhere near it.

Handicaps

Strong players can offer weaker ones a handicap, to keep the game interesting. Usual handicaps are "two Lions", where the weak player starts with his Kirin promoted, and "three Lions", where the weak player starts with two promoted Kirins (one replacing the Phoenix), while the strong player takes the two unpromoted Phoenix. A lesser handicap is "two Kings", where the weak player starts with the Elephant promoted.

Some thoughts on the Lion-capture rules

The rule that any significant piece can act as a 'capture bridge' between two Lions might at first seem strange, as who would voluntarily place a valuable piece next to an enemy Lion, where it could be annihilated on the spot? Its necessity can be understood from the principle that Lion-capture restrictions should have as little impact on the game as possible, apart from preventing Lion trading. Without the bridge-capture rule such an unwanted side effect would occur in the following situation:

When an unprotected Lion threatens to take an adjacent piece in passing, it would be possible for a defending Lion to step next to that piece on the other side, under protection of something, after which there is no way for the attacking Lion to withdraw out of reach of the defending Lion after taking the piece it threatened with its first step. Without the anti-Lion-trading rules, it could simply have captured the adjacent piece, and then traded the Lion in its second step, which would have gained him the piece. So the anti-trading rule would facilitate defense, and the bridge-capture rule repairs that.

The bridge-capture rule makes that a Tokin is not fully upward compatible with a Pawn: the Pawn can stand between Lions without offering the opponent the possibility to trade, but a Tokin cannot. This can be a reason to defer promotion of a Pawn (and one of the historic mating problems is based on that). And because of this, there has to be a special promotion rule for unpromoted Pawns reaching last rank, while the attitude towards Lances apparently has been "just don't do it!".

A Lion superficially seems to have all moves of the Kirin, and more. But also here the anti-trading rules spoil this: a Kirin can capture a non-adjacent protected Lion and be captured without triggering the counter-strike rule, whereas a Lion cannot do either of those. This can be a reason to defer promotion of a Kirin.

The Japanese Chu Shogi association has adopted the 'Okazaki rule', known to have been invented in recent times: retaliation against a Lion immediately after your own Lion is captured would be allowed if the opponent's Lion is unprotected.

This 'user submitted' page is a collaboration between the posting user and the Chess Variant Pages. Registered contributors to the Chess Variant Pages have the ability to post their own works, subject to review and editing by the Chess Variant Pages Editorial Staff.

This 'user submitted' page is a collaboration between the posting user and the Chess Variant Pages. Registered contributors to the Chess Variant Pages have the ability to post their own works, subject to review and editing by the Chess Variant Pages Editorial Staff.

Author: H. G. Muller.

Last revised by A. M. DeWitt.

Web page created: 2015-03-16. Web page last updated: 2024-07-25